He Just Needs to Try Harder! The Struggle to Understand and Develop Executive Function Skills

Justin, a copper haired, lanky 5th grader with a passion for basketball, plopped down his over-flowing backpack and made his way to the breakfast table.

“Why are you only wearing one sock?” his mother asked, her brow furrowed in frustration. She shook her head as Justin ran back upstairs to retrieve his sock. She’d already told him three times this morning to get ready for school. Unfortunately, it was just another day of trying to get off to school on time with a brilliant child who couldn’t organize his backpack, remember to brush his teeth, and figure out all the steps needed to finish his assignments. Nor could he slow down his mind and keep himself focused at school. Justin was brilliant and it wasn’t just his mother’s opinion. For the last five years his teachers commented on Justin’s high level of intelligence, if only he could remember his homework, keep himself organized and stay focused he’d be a much better student. Was Justin just lazy? Did he not care about school? No, his mother thought. Justin wants to do well and even gets frustrated with himself. Then why?

Justin’s difficulty stems from weakness in Executive Functions, the mental processes that enable us to plan, organize, focus our attention, prioritize tasks, set and achieve goals, control impulses, and handle multiple tasks successfully. Many parents and some teachers do not understand that these functions are not necessarily innate and automatic. Instead they might assume their child is lazy or not trying hard enough. They give consequences for failure to organize himself or get somewhere on time. Perhaps they try rewards that seldom work. Without understanding the cause of his behavior and providing direct support, parents and teachers will see little improvement in his executive function skills.

Just as learning differences like dyslexia are caused by neurological differences in the brain, so too is weakness in executive functions. “Research in animals indicates that the prefrontal cortex is very sensitive to its neurochemical environment and that small changes … can have profound effects on the ability of the prefrontal cortex to guide behavior.”(1) Executive functions require a coordination of several areas of processing including memory and speed of processing. Disruptions in the neurochemical environment of the prefrontal cortex upset the necessary delicate balance of chemicals needed to successfully coordinate these processes. Problems can be seen at any age but are more apparent as children move through the school years as demands increase. Further, stress has a profound effect on the brain’s ability to process, store and retrieve information necessary to executing tasks. Students who experience instability, chaotic home environments, and trauma are especially prone to delayed development of executive functions. As with other learning differences, disorders in executive function can also run in families, (2).

That takes me to the first and most important factor in developing executive functions. Consistency, routine and structure at school and at home are two factors that greatly influence a child’s ability to develop strong executive functions. According to the Harvard University Center on the Developing Child, stability in relationships and environment, along with routines in the home have a profound impact on a child’s development of executive functions.(3) As a parent, creating routines and structure around schoolwork can improve your child’s ability to be successful in school. Therefore, be sure that your child has a consistent setting, free of distractions to do homework. Be sure to establish a regular time and routine for completing homework. Limit distractions by turning off the TV, removing cell phones and other devices not necessary for the task, and ask other family members to limit distractions and disruptions.

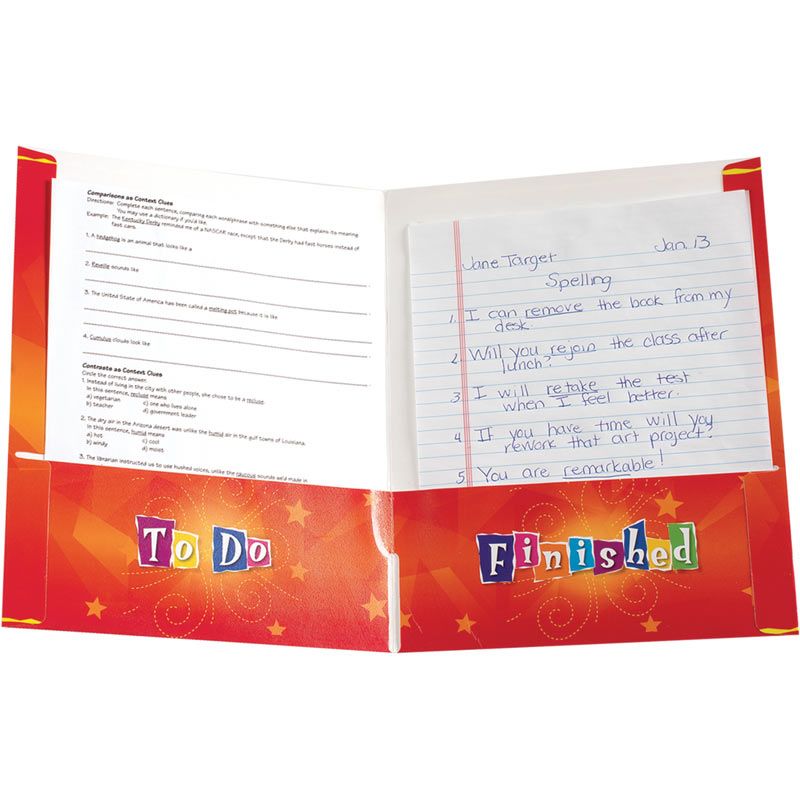

When working with a student to improve executive functioning, it’s best to focus on one skill at a time. The primary difficulty for students with weakness in executive functions is in keeping work organized and handing in completed assignments. It’s important to establish a simple and consistent system the student can use throughout his school years. Often I use a two pocket folder stystem. When opened, the pocket on the left is labeled “work to do” and the right side is labeled “work to hand in.” When a student receives an assignment, it goes in the “to do” side. When complete, it’s placed in the “hand in” side.

Next, the student has to establish the routine of using the system. I can’t just tell him what to do. I need him to really know and understand so I walk him through the process by having him act it out and explain each step. For example, we might be seated at a table and I’ll be the teacher handing him a worksheet of math problems. The student would say, “I put the assignment in the ‘to do’ side so when I get home I know what I have to do.” He then places it inside the folder. Then the student pretends he’s getting home and beginning his homeowork. He goes through all of the steps, verbalizing each one as he does so. Finally, he recaps the steps in sequence for me.

The following day we check in and perhaps we will do another task in which he lists all of the steps and draws a quick picture for each step. Another occasion I might ask him to teach me the routine. I will continue with these exercises until he has internalized the process and is doing it automatically.

Learning executive functions requires coordination between home and school. Teachers, care-providers, and parents need to work together to enforce the routine until it becomes automatic and internalized. Without this, the child will likely not be successful in the development of these skills. Routines and structure are paramount to success. Remember, work on mastery of one skill at a time.

Should you reward your child for success? If you want to, but be sure to help your child recognize internal motivators and intrinsic rewards. Life does not always give us tangible rewards and the most impactful rewards are the emotions and esteem that come with success. Students should recognize that the real reward is less stress and more success.

To summarize:

- Establish a consistent routine and environment for completing homework

- Coordinate efforts with all care-providers and instructors

- Focus on one step at a time

- Create a two-pocket folder system

- Practice the steps

- Have students verbalize and act out routine

- Have students teach you or another person the routine

- Practice every day until internalized

- Emphasize intrinsic rewards

Next time I will cover another aspect of executive function, time management.

References

Neurobiology of Executive Functions: Catecholamine Influences on Prefrontal Cortical Functions. Arnsten, Amy F.T. et al. Biological Psychiatry , Volume 57 , Issue 11 , 1377 – 1384

Executive Function & Self-Regulation.” Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University. Harvard University, n.d. Web. 12 Jan. 2017.

“Executive Function Fact Sheet.” Executive Function Fact Sheet | LD Topics | LD OnLine. National Center for Learning Disabilities (NCLD), 2008. Web. 12 Jan. 2017.

Dawson, Peg, and Richard Guare. Smart but Scattered: The Revolutionary “Executive Skills” Approach to Helping Kids Reach Their Potential. New York: TheGuilford, 2009. Print.

About the Author

Donna Austin has worked in the field of learning disabilities for over 20 years, both as an Educational Therapist and a credentialed Special Education teacher. She is currently Assistant Director of Bayhill High School, a high school for students with learning differences. She can be reached at austin@bayhillhs.org.

[…] This makes homework especially difficult…for them and you! Want to ease the frustration of homework? Try implementing these five […]